As an only child raised in the suburbs of New Jersey during the early ’90s, my entire world revolved around American Girl. I knew every doll by name and committed each of their stories to memory. I obsessed over their stylish outfits (and the interiors of their bedrooms) while simultaneously learning American history. Sure, I struggled to accept the fact that Addy Walker was my only option for representation as a young Black girl, but I was inspired by her empowering story of survival in the Civil War era.

I eventually made the pilgrimage to American Girl Place in Chicago, and then to the New York City location when the retail stores expanded access to the full AG experience: shopping at the store, eating at the cafe, getting dolled up at the salon, and sending your doll to the hospital for a full body reboot. Clearly, American Girl culture was a highlight of my childhood, and I’ve welcomed the current dollcore renaissance with open arms.

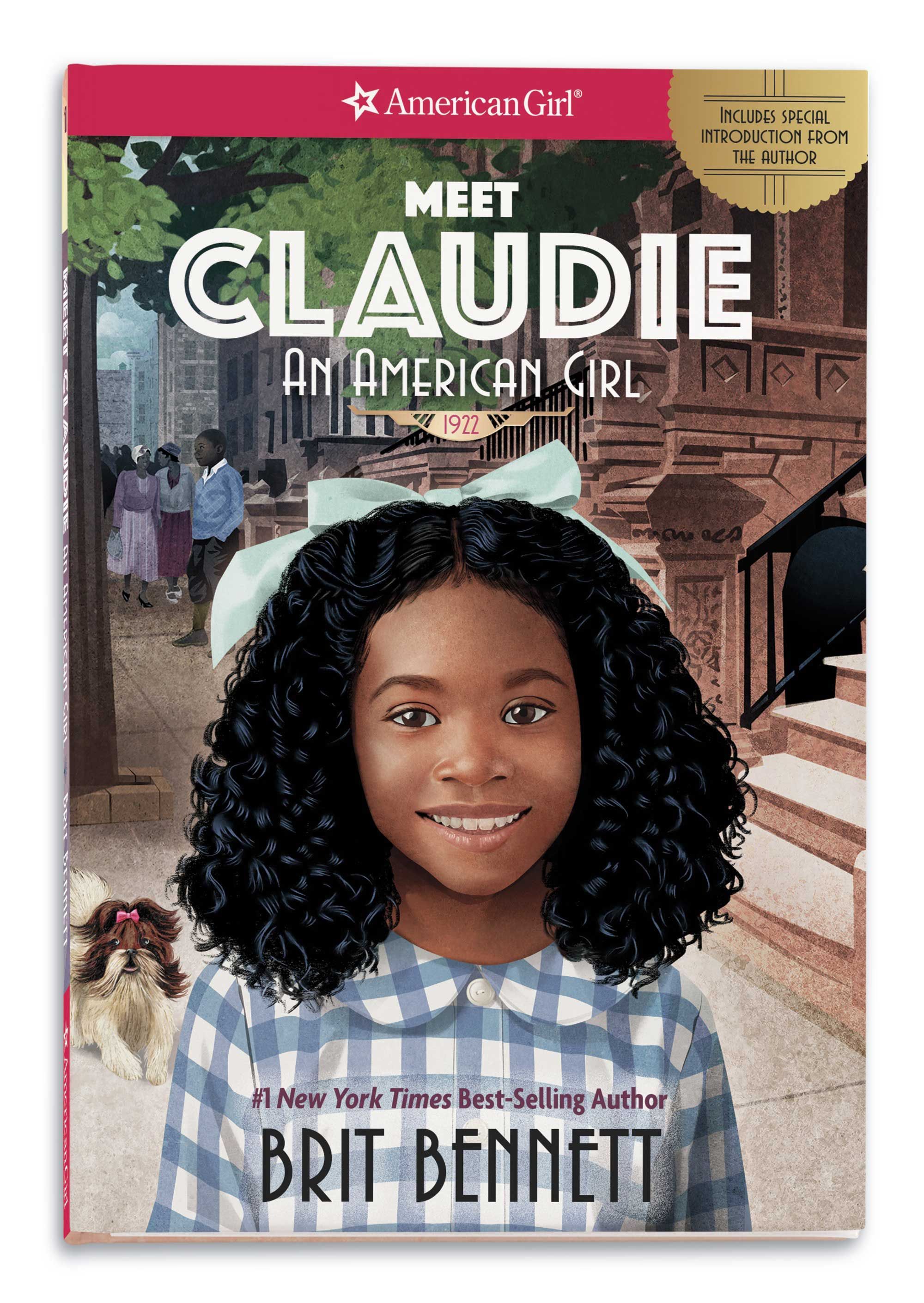

A millennial herself, Brit Bennett also grew up on American Girl and was immersed in every aspect of the franchise, from the books to the dolls (she shared an Addy doll with her sister) to the theater kits, which included scripts and a director’s guide for a four- to five-act performance based on a doll’s backstory. Now 32, the best-selling author of The Vanishing Half and The Mothers is still a huge AG fan. In 2016, Bennett tweeted about wanting an American Girl doll deal. Six years (and many more tweets) later, she manifested that lifelong dream through Claudie Wells, the newest historical character to enter the AG universe.

More From ELLE

Claudie’s story takes place during the Harlem Renaissance, one of the most pivotal movements in Black history, which saw a confluence of civil rights activism, a national housing crisis, and the Great Migration. But to nine-year-old Claudie, finding her unique talent amidst a vibrant community of artists is paramount.

Claudie’s arrival at the AG brand makes her the fourth Black doll in the historical line, following Addy’s debut in 1993, Cécile Rey in 2011, and Melody Ellison in 2016. During the launch party for Claudie at New York’s American Girl Place late last month, Bennett met Connie Porter, the author of Addy’s beloved book series. “It was surreal to meet somebody who wrote something that meant so much to me as a child,” Bennett says on a Zoom call from Los Angeles. “She talked very candidly about her experience when those books first came out, about the pushback she got, the criticism, and everything. It was very cool to meet her and to think about how my book could influence somebody who’s growing up today.”

Read on for a conversation with Bennett about the making of Claudie’s story, including how the author was able to maintain a sense of playfulness and joy while also teaching young readers about some of the most difficult aspects of American history.

How exactly did this opportunity with American Girl come about?

After I wrote an essay about Addy in 2015, my friends started sending me American Girl memes. It was something people began associating with me. During a podcast interview, I was asked, “If you could write your own American Girl doll [story], what would it be?” It was something I’d never thought about before, and I feel like that conversation spurred my tweet in 2016. I think eventually one of my tweets caught somebody’s attention at American Girl, which I obviously didn’t expect—you know, you’re just talking on Twitter. After that, somebody reached out to me, and we started discussing the possibility of doing a new historical character, which was a culmination of both my childhood interests and adult interests.

Could you walk me through the process of developing the tale of Claudie Wells?

It was a very involved process, I had never worked in a way that was quite so collaborative before. There was a board of historians and somebody who could help me research. It was a long process of meeting with the historians and talking about the nuances of the time period, and a lot of back and forth of trying to develop the story in a way that would be really interesting for young readers, but also would teach about this time period. It was such a nice gift to be able to tap into the knowledge of experts rather than just Googling on my own.

Was it hard for you to keep quiet about it?

Yeah, it was very different from my typical experience of publishing books, where you want to shout it from the rooftops so that as many people know about it as soon as possible. So much of the process of publishing a novel is forcing people to read it really early on. It was really fun the day that the book came out to see everybody react to it because it was sort of this two-for-one of “I did this book, and it’s out today.” It was exciting to see people react to that. I imagine it’s like surprise releasing an album, which is very different from the very long, drawn out, slow process of publishing a novel where you’re talking about the book for six months before it ever hits the shelves.

What was your experience like on release day?

I did a signing at the store, and one of the cool things for me was that I feel like half the people getting books signed like were parents and children, and the other half were millennials. Some people were familiar with my other work, but other people were just excited that there was another book. It was cool to make something that made people so happy. It’s not that I have never experienced that before with my novels, but it was a different level—people were really emotional. There was this guy there, maybe in his 20s or 30s, who told me that he was buying the doll for himself. He was like, “I always wanted an American Girl doll when I was a kid, but I wasn’t allowed to have one.” To see the children with the doll, of course that’s really moving, but it was also moving to see millennials there, who were often a little sheepish or embarrassed, but also very happy to re-experience this thing that made them happy as children.

Claudie’s story takes place in 1922 during the Harlem Renaissance. What about that particular era intrigued you?

It was a time period that I just found really interesting, in part because of the contradictions. The fact that you had this outpouring of Black creativity, which coincided with the rise of lynching in America. These things are happening at the same time, and they’re informing each other. There were some moments where my story ideas informed the direction of the research and other moments where the research informed the direction of the story. Speaking with the historians, I learned how the Harlem Renaissance was an era where there became this renewed focus on the importance of Black childhood. This was a moment in time in which people really focused on teaching Black children pride. And of course the story of Harlem is a story of housing and housing segregation. So I was thinking about all of those large topics, and then thinking about the specifics of the character who is growing up surrounded by all of these very talented people and worrying that she is the only person on the face of the planet who doesn’t have a talent. I wanted to balance her individual journey as she tries to figure out who she wants to be and what type of art she wants to put out in the world with these larger systemic questions that are pressing in on her world.

In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, the author Emilie Zaslow points out how “there’s been a call for the story of an African American girlhood that’s not filled with struggle” and instead focuses on the Black experience as something to be celebrated. How did you go about finding a balance for Claudie’s narrative?

I hear people say that often, not just for stories about children, but this [idea that] “we’re tired of stories of Black struggle; we want to see stories of Black joy.” It’s a difficult thing because all stories have tension, all stories have conflicts, all stories have some type of problem that must be solved. In particular if you’re delving into history, it’s hard to write that story that is just “Claudie running around Harlem doing whatever” when every day she’s walking past a banner that says “a man was lynched yesterday.” I wanted to be mindful of the fact that these books are for young readers, and part of the pleasure of these books, at least for me, was disappearing into the fantasy and the playfulness of that. But at the same time, I felt like I couldn’t do it without being truthful to the reality of that history. At one point, I asked the historians, “What would a nine-year-old in Harlem have understood about X, Y, Z?” It kind of felt like, “Well, who am I to assume that a nine-year-old today couldn’t understand what a nine-year-old 100 years ago had to understand?” It’s a difficult balance in that way, but I wanted to maintain Claudie’s spirit, creativity, and her joy, while she also is learning about these difficult histories that have influenced her current life.

What are you hoping young readers will take away from Claudie’s story?

Falling in love with books, enjoying to read, and being entertained, I think that’s so important. So I hope that they’re entertained and enjoy reading the book. In the beginning of the book, Claudie is very caught up on this fact that she feels like she’s not special. She has this anxiety about it and she also feels like if you try something and you’re not instantly good at it you should stop doing it. One of the things that I miss so much about childhood is not having as much self-consciousness as I do now. I hope that that’s one of the things young readers take away, sort of falling into the things that you love or the things that interest you with abandon and not worrying about whether you’re good at them. If you like to sing then sing, don’t worry about what you sound like. I think that’s part of Claudie’s journey, finding ways to push through her anxiety and fear about not being good enough or people laughing at her. Anybody can be an artist—it’s just about doing what you love and creating something beautiful for the people you care about.

Sydney Gore is a writer, editor, journalist, and consultant based in New York City. Her work has been published at The New York Times, Vogue, Wall Street Journal, The Cut, W Magazine, Teen Vogue, Vox, MTV, Rolling Stone, The FADER, and more. Sydney currently works as a Digital Design Editor at Architectural Digest where she brings a fresh perspective to the table through dynamic stories that are shifting the culture.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/01/15/049/n/1922564/a753b85967884eaf8fe5f9.34920179_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/01/15/863/n/49352476/9e69ba8767880fdc9084b2.84057222_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/01/07/813/n/1922564/b63421d9677d72ddd6eff7.56786871_.png)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/12/24/622/n/1922564/9eb50f2c676abd9f1647c5.05876809_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/12/12/709/n/1922564/7bb19976675b0904d64976.02429851_.jpg)