In recent years, classic Mexican horror has gained a deeper appreciation and curiosity from international horror audiences wanting to experience the unique terror of Mexican horror.

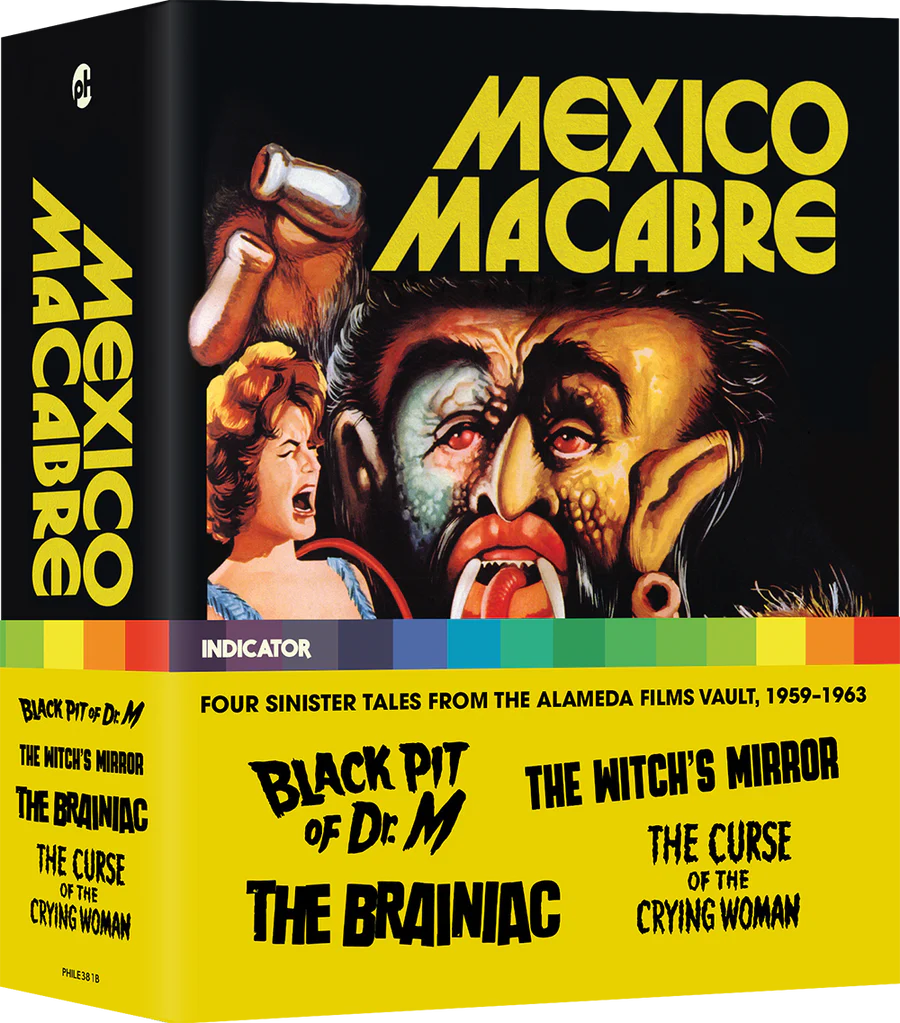

Mexico Macabre: Four Sinister Tales from the Alameda Films Fault 1959-1963, the box set released by Indicator, highlights four iconic films from the golden age of Mexican horror cinema, Black Pit of Dr. M, The Witch’s Mirror, The Brainiac, and The Curse of the Crying Woman, from the influential Mexican production company Alameda Films. These films broke boundaries and pioneered new artistic styles in Mexican cinema, blending the influence of gothic imagery from American and European cinema with Mexican culture and history. The artistic influences of these films can be seen deeply embedded in the horror films and filmmakers of Mexico from the gothic style of Guillermo del Toro to the modern trailblazing Mexican horror films Tigers are Not Afraid and Huesera: The Bone Woman.

Taking us into this journey of classic Mexican terror is Mexico Macabre producer Abraham Castillo Flores. Castillo Flores, a Mexican film historian and curator, has spent his career promoting the history and artistic significance of Mexican horror and genre cinema. His previous endeavors include being the former Head Programmer of Mexico’s Morbido Fest and a guest curator for the Academy Museum of Motion Picture series Mexican Maleficarum: Resurrecting 20th Century Mexican Horror Cinema.

In our interview with Flores, he shares with us how he gained his appreciation for the genre, the impact that producer Alfredo Ripstein and Alameda Films had on the preservation and rerelease of these films, and the importance of creating a greater awareness of these iconic films.

Bonilla: How did you become interested in Mexican genre cinema?

Castillo Flores: Well, I would have to blame TV movie nights with my grandmother Gloria when I was a young child. I have to confess that at the time, like a lot of people from my generation, I tended to look down upon Mexican horror films just because they did not look as slick as the American films and the SFX were not awe inspiring usually quite the contrary. But it was my grandmother who was a teacher and very interested in myths and legend who made me consider these movies from another point of view.

After watching the films, she would tell stories about the legends that had inspired them and some of the historical figures that were sometimes mentioned. If ghosts were mentioned in a film, she would casually tell me she had seen the ghost of her father a few days after he passed away. At the time those stories frightened me. I was very scared of watching Mexican horror movies with her because of the post-film chats. But as you can imagine the impressions that those movie nights left on my psyche are still very close to me. In fact, the fear of some of those films combined with my grandma’s stories kept me away from genre cinema altogether for quite a while. But when puberty hit, my attitude towards horror cinema changed and I gorged. I still had a somewhat distant relationship with Mexican Horror Cinema.

Years later when I went to continue my studies in the US, the distance gave me a very curious perspective in my appreciation of my country and all of its’ vast culture. Little by little a shift happened within. When I rewatched many of those films I went beyond the low budgets and the crappy effects, and realized how much bravado and imagination filled them. Our cinema industries are quite different. It’s not the same to do movies in Mexico that is to make movies in Hollywood. The cameras are the same, the system is the same, but the budgets, the distribution, and the scope of them are different.

It dawned upon me that Mexican film directors and producers were really trying to do big stuff. They had great imaginations, but sometimes they didn’t have the budget, so they didn’t have the means to do them. But that didn’t deter them. Quite the opposite. They were like, “Okay, we’re going to do them. I want aliens, so let’s get aliens. They look shitty. Doesn’t matter. Just take a leap of faith. I want aliens, I will have aliens.”

The fact that you are not defined by the amount of budget that you have, and you still find a way that your imagination ends up on the screen somehow, is quite magical. I love that about cinema. I think that’s one of the things that we have to come back to is that cinema should not replicate reality. There’s a lot of reality around. Cinema should be or can be the realm of dreams or nightmares. And in that sense, it’s easier to talk about reality when you’re not addressing it directly. That’s why I love genre cinema so much because it becomes a dimension where you can explore.

The Mexican way of doing the nightmare and the dream worlds, it’s amazing, not only because of our traditions, our costumes, but dare I say our craziness or zany way of doing things or finding a way to do it. No matter what. Mexico is a clash of cultures. Even though the conquest happened a long time ago, I think these two sides are in constant communication /clash and you see it especially in horror movies. So, it’s become fertile ground.

Why is it important to bring attention to Mexican horror cinema?

It dawned on me that while I was celebrating genre cinema from all over the world while I worked in Morbido, there was so much more I could do to bring awareness and respect to the Mexican horror genre, which sadly is still looked down upon by certain critical circles, institutions, and historians. The work of so many important filmmakers and actors was being sidelined and forgotten. I became obsessed with the idea of resurrection of certain titles and filmmakers which I was sure had a lot to say in this day and age.

My quest right now is to say, “Look, there has been a lot of people who crafted and erected the Mexican Film Industry whom are widely celebrated, but why do most historical chronicles do not mention people like Abel Salazar, Fernando Méndez and Chano Urueta?” By doing the crazy stuff, the extra weird, their work left an imprint of Mexican nightmares all over the world. They might have not won awards or respect, but people went to watch the movies and they left a deep footprint. Most people forget that Guillermo del Toro comes from this line of dreamers. This line of people who go against what the industry wisdom tells them what works.

Some people ridiculed Guillermo del Toro in 1992 when his movie Cronos came out. His producer Bertha Navarro and him had a really hard time bringing that movie to life. They made fun of them, like, “How dare you do something like this. Nobody’s gonna go watch it. We don’t do these types of films in Mexico.” And look where he is now. I think celebrating that, applauding not following anybody and carving your own path is very important. I feel it is paramount to celebrate the trailblazers who opened the path, who have been forgotten and whose work is due for resurrection.

Most cultural institutions are not really interested in doing this. They tend to think it has no deep cultural importance. It’s only certain companies with a long history in Mexican Cinema, that understand the legacy these films hold. So, it was crucial for me to find people who cared about this legacy and Daniel Birman Ripstein from Alameda Films was someone who actively responded and became a key ally to this quest of mine.

How did you become a part of this box set?

Part of this idea of celebrating Mexican cinema, I realized very soon that there’s two ways when you can do that. One, is to show the movies again theatrically, which is very hard. You can do it in museums and festivals. I worked in a film festival for the last 12 years. But I also realized that the scope of that was a bit limited.

Two, the Blu-ray and the collectors, that’s another big part. Also, it allows you this idea of doing special features, of doing new documentaries that can enlighten people on how they were made, and the people behind them. I got very interested in doing that. So, I started working on that idea.

I have to say it is all thanks to Kier-La Janisse, she’s the one who first brought me into the realm of special features in blu-rays. I did something with her for the special features of Perdita Durango for Severin Films. The she interviewed me for her phenomenal documentary, Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched. Afterwards, I started getting asked to participate in more Blu-rays.

And that’s how I first got in touch with Indicator. They asked me to be part of Llorona and Phantom of the Monastery releases. From that, they said, “You’re really big with the history of Mexican horror cinema and you have a lot to say. Maybe you could bring that energy to other films.”

I was already curating Mexico Maleficarum [for The Academy Museum] at that point, and I knew that Alameda Films, not only do they have a treasure trove of Mexican films, but they’re also interested very much in the preservation and celebration of the legacy. These films should not just be there on the shelf, they be showing their magic. So, that’s when I talked to the grandson of Alfredo Ripstein, Daniel Birman Ripstein, who’s now the president of Alameda Films and said, “I think there’s an opportunity to do this.” That’s how we got together with Indicator and this idea of doing the box.

I don’t want these stories to get lost, if I have a chance right now, to bring them somewhere where they can be recorded for posterity and be given widespread distribution. That’s something that is very important. I think that can be my contribution to Mexican film history. If I can keep these stories from being lost, because there’s no one in Mexico right now that is putting in the money to do it, so there’s these Blu-ray releases that can make that happen. I am delighted to be a part of that endeavor.

How important is it to preserve these types of films?

Alameda Films has been incredible. As Mexico Macabre is concerned, it would not exist without their cooperation and without also their understanding of the importance of legacy.

In 2023 Alameda Films celebrated their 75th anniversary. The founder of this company, Alfredo Ripstein, totally understood not only the business of filmmaking, but he understood the importance of genre. For example, he loved cowboy movies and he was a great producer. He liked to delve into those movies that could bring him closer to his passion. On that same note, he understood that horror was good for business.

Abel Salazar was his very close friend. When Salazar later in life didn’t want to deal with the movies anymore. He went to his friend Alfredo and he sold some of his key film like El Vampiro, El Espejo de la bruja (The Witch’s Mirror), and La maldición de la llorona (The Curse of the Crying Woman) to him. He said, “Alfredo, I trust you that you’re going to take care of these movies, not only now but for the future.”

And that he did but I have to add that Alfredo Ripstein also taught and shared this respect for legacy and history to Daniel Birman Ripstein, who not only took care of the movies, but he’s an integral part of the boxset. He understood that legacy by keeping these movies alive and knew that there was interest beyond the frontiers of Mexico for these types of stories.

El Vampiro for example, in 1957 changed what horror movies were because there hadn’t been any horror movies that were so big box office wise. So, after that everybody got into the horror movies in Mexico. It opened up a golden age. It’s just a few years from 1957 to like 1964. And of course, it continued, but there’s been ups and downs. But that was a crazy moment where everybody was doing the horror movies, including Ripstein. He produced Misterios de ultratumba (Black Pit of Dr. M), which in my personal view is the jewel of the crown of the boxset.

The book in the set has a chapter about the Mexican monster makers. Why was it important to include that aspect of filmmaking?

One of the things that I’ve experienced working in film festivals for so long is that our industry tends to always glorify actors and directors, which I understand why it does. But we keep forgetting that movies are a team effort. And within that team in horror movies, the people that do the special effects and the special effects makeup are important, they are crucial.

As I’ve been doing research, I was like, “Why do we not know the names of these people that have made the monsters here in Mexico?” I know our monsters are not the most important ones, but still, we need to know why we don’t know them. It was super sad to find out that there’s no pictures of them. There’s no information about them. And it dawned on me that these stories are lost.

If any new information comes in, we need to find a new place for it. I think it’s important because every person that worked on these movies left their imprint. There are names like Juan Muñoz Ravelo, the guy who made the special effects in practically in every horror movie in Mexico. He did outlandish, crazy stuff. I think he should be celebrated. Because he made the monsters in Mexico, for better or for worse. People like him are the ones who visualized and crafted the monsters. Guillermo del Toro is part of that legacy. Most people forget that he started as a special effects makeup man. His passion for monsters and love for creatures is what drove him to filmmaking.

In the special features of this box set, there are interviews from film scholar Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro and the daughters of actress Rita Macedo, Julissa de Llano Macedo, and Cecilia Fuentes Macedo. What was it like conducting those interviews?

Well, on the side of Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro, it was a highlight of my career, because he’s one of the film historians that I admire the most. His work is incredible. He’s not only savvy, but how he connects the history of filming in this country [Mexico], through the history with political intrigue, historical movements, and weaves them all together.

When you read his books, you understand how many of the films are important, show certain aspects of our history, and who made them. So, having an excuse to go and interview him at length about this stuff that he’s so passionate about was super exciting. But most importantly, I think it’s a chance for people outside of Mexico to know to get to know him, because he’s a brilliant and passionate man. The fact that we can bring attention to our national film historians and present them to an international public, is marvelous.

On the other side, the daughters of Rita Macedo, that was a dream come true for me. There’s a book called Mujer en papel, which is the book that Cecilia Fuentes Macedo published. Her mother left them an unpublished book. And Cecilia fought for years for that book to come out. When I read the book, I was flabbergasted. It really showed another side of the Mexican show business that nobody had been there to document that well. To me, it was important that she was involved with this somehow.

I thought it was super important that Cecilia and Julissa had their say. You had to have their stories so they could talk about their mother, because each of them has a very different view of who Rita Macedo was. And even though it’s a story full of sadness, grief, and tragedy they’ve managed to transcend it and they are more than delighted to share it.

The beautiful thing is that her family has touched upon literature, theater, television, and popular music, to a degree that is crazy. Very few families, I think, have had such a deep impact in the culture of Mexico.

I knew that when people saw that special feature, not only would they look at the movie differently, but they would understand Rita Macedo through for another perspective, and hopefully, and this is my fantasy that someone in the States or England will say, “We need to get that book translated.” Rita Macedo should be a household name as popular as Maria Felix or Dolores del Rio.

What’s something you want audiences to take away from this box set, especially those who are not connected to Mexican culture?

I want them to be curious like, “Oh, I should look more into Mexican cinema. I want to try more of that.” There are diehard fans, there are people that already know about these movies and are keen to watch them. But I think that the most important part of all this endeavor, especially in the future, is we need to get more people to be aware their existence. And if they’re curious, and they like the flavor, they want more. That thought gives me fuel to keep on doing it.

And this is something very personal. There’s this idea for me, of looking back and seeing a family. This is a film family that created horror that believed in these stories. They created a part of the industry that still to this day is still alive. Because of these films, despite the scorn of critics, the oblivion of history, the bad mouthing from certain parts of the public, they’re still there and they have a lot to show us.

—

Mexico Macabre was released on Blu-ray by Indicator / Powerhouse.