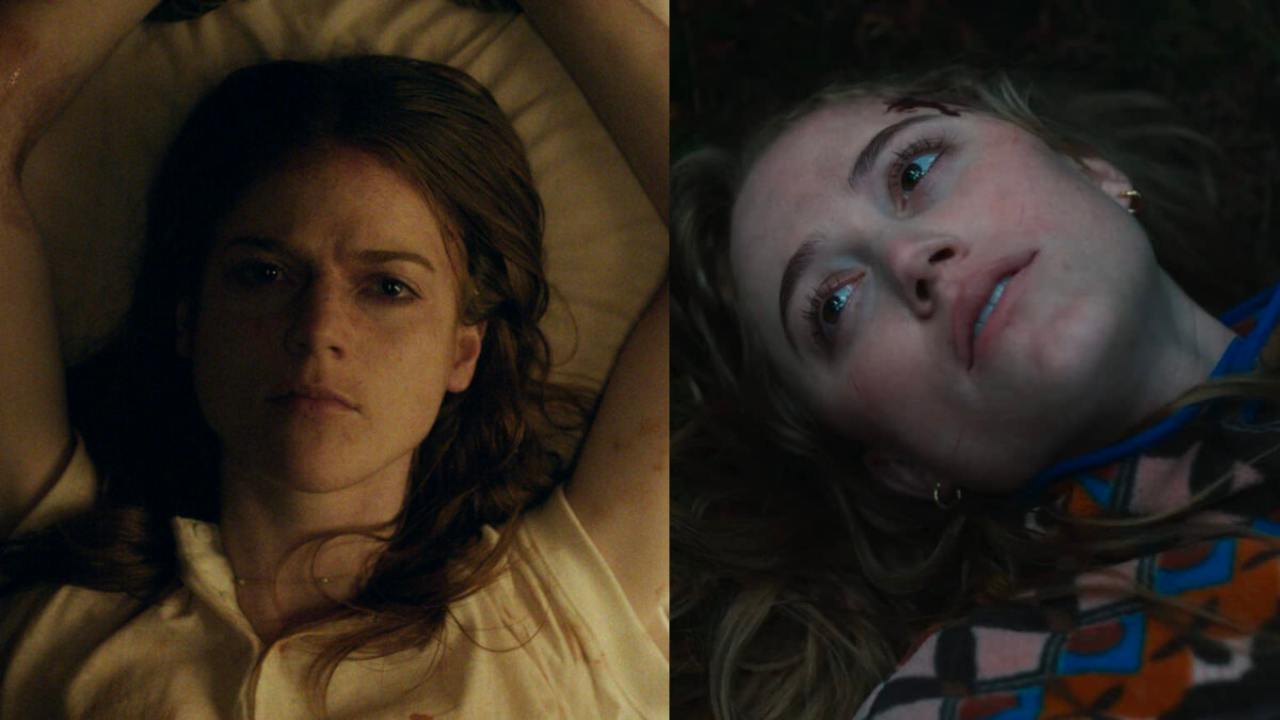

“I haven’t been feeling like myself,” Ruth says in Significant Other, a line that suits Bea in Honeymoon like two peas in an alien pod. Though released eight years apart, Dan Berk and Robert Olsen’s Significant Other shares uncanny DNA with Leigh Janiak’s Honeymoon. Both stories follow two lovers on a sabbatical in the woods, on the precipice of the next step in their relationship, and shine a spotlight on their love and commitment as they face the alienation of being alone together. Neither couples are fully aware that aliens are indeed out there, though it’ll be part of their undoing. Significant Other and Honeymoon are sci-fi horror soulmates; the anti-date movie double feature.

In Significant Other, Harry (a killer Jake Lacy) has roped his partner Ruth (Maika Monroe) of six years into a backpacking trip. They say the couple that camps together, stays together. Harry is cheery en route, while Ruth is profoundly anxious, burying herself in an encyclopedia about all the flora and fauna they might encounter to soothe her nerves. Or because she knows what the trip is really about.

Panoramas of the Pacific Northwest and static close-ups compliment Harry and Ruth’s easygoing banter on the trek, signaling stability in their relationship. When they reach a scenic cliffside and Harry gets down on one knee, we veer from breezy romantic comedy to Ruth’s inner horror movie. We experience the proposal from Ruth’s POV, the camera tethered to her equilibrium like a contestant on MTV’s Fear, and she nearly falls head over the cliffs.

The proposal goes better for newlyweds Bea (a luminous Rose Leslie) and Paul (Harry Treadaway) in Janiak’s 2014 debut Honeymoon. They have a weekend to themselves where the only itinerary is exploring each other’s bodies. If Harry and Ruth are the chill couple, then Bea and Paul are insufferable in their marital bliss. They nuzzle their noses, stare longingly into each other’s eyes, have shower sex, and dare to skinny-dip in the lake. Janiak’s camera is handheld and full of movement once we arrive at Bea’s family cabin, sweeping us into their Nicholas Sparks romance. Composer Heather McIntosh’s delicate score accompanies their frolicking around the cabin. It’s when the music stops that Janiak zooms in on the cracks in their dynamic.

Paul comments on Bea’s “womb” while making breakfast the next morning, a reference to their carnal activities, and it unintentionally fills the cabin with pressure. The question of having a baby already dawns on them on day one—a presumption that comes with their nuptials as readily as the rice throwing and the cans tied to the car.

Marriage and children have been the longstanding markers of adulthood, a societal norm that Bea and Paul know implicitly. They seem like children themselves, with the pet names they have for each other (Honey Bea, Pauly Poo), or racing each other to the door. Their awkward stumbling on the topic says everything. They’ve never thought about starting a family until now, and the prospect is terrifying. Paul cuts the tension saying they have plenty of time to discuss it: “We’re gonna have breakfast together every day for the rest of our lives.” What’s meant to be an extension of their marriage vows instead sounds like a domestic trap. They’re supposed to be having the perfect honeymoon. For a brief second of miscommunication, they crash-land back to reality.

That night, Paul finds Bea naked and alone in the woods, bearing strange marks on her thighs. A mysterious light lured her outside, where otherworldly visitors invade her body and impregnate her. Bea claims she was sleep-walking, while Paul says she’s never sleep-walked before, and this inexplicable event plants the seeds for their unraveling. Unbeknownst to Bea and Paul, they’re no longer on their honeymoon, just as Ruth and Harry aren’t on a romantic escape in the woods. Both couples are at the beginning of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Jack Finney’s 1954 novel The Body Snatchers has been adapted into four films, laying the foundation for the alien invasion movie as we know it: both the 1956 and 1978 versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the 1993 Body Snatchers, and 2007’s The Invasion. (The tagline for the 1978 movie read: “Watch out! They get you while you’re sleeping!”) Finney’s story introduced the premise of the “Pod People,” alien plantlike spores that descend on Earth and grow into large seed pods that produce human replicas, though devoid of emotion and anything that resembles humanity inside.

There are aliens that abduct (The X-Files), and aliens that exterminate (War of the Worlds and Independence Day); the Pod People are the passive-aggressive of the bunch, taking over a population by assimilating into society. The premise is a literal body horror scenario that comes part and parcel with the themes of paranoia. The aliens take over our bodies and something unspeakably monstrous hides within. Our original bodies disintegrate, and the surviving humans can’t trust anybody until there’s nobody left.

Though Honeymoon’s setup conjures a mood board of cabin-in-the-woods horror movies, Janiak remains firm on the over-the-shoulder paranoia inherent to the subgenre. Invasion of the Body Snatchers brought the fear of the masses and conformity, the distrust of loved ones, friends, and neighbors. Honeymoon and Significant Other zero in on a loved one and a different kind of conformity, putting the fear of marriage under the microscope with a millennial lens. Love is its own bodily takeover, and coupling is akin to losing one’s identity to another. We become eerily like our partners in the process, adopting their habits, finishing each other’s sentences, etc. Marriage is a courtship you both enter with complete trust and understanding. It’s disorienting, then, to find that you don’t know your significant other as well as you think you do.

Harry thought they were ready to take the leap, ideally wanting to be at Bea and Paul’s idyllic cabin on the lake. Ruth, however, is content where they’re at in their shape-shift tent. They only have each other out in the wilderness, and thus, have no choice but to confront their baggage. Harry calls out Ruth’s fear of commitment stemming from her parent’s divorce. He insists they won’t end up that way. But for Ruth, marriage is the ultimate prison.

There’s a double entendre in the film’s title. The term “significant other” implies the looming topic of marriage between long-term partners. This comes with the invisible, ever-present societal expectation to tie the knot at a certain age, one so embedded in our consciousness that it’s presumed the moment we’re dating someone, whether serious or casual. We date to find “the one,” get married, start a family, and so on. We’re told marriage is the key to happiness and unlocking the rest of our lives. It’s hard not to see the setup from Ruth’s perspective. Because these structures are implied and maintained from generation to generation.

The conformity in question is whether she’ll marry like everyone else. She’s rendered as the “other” in the equation, while Harry is considered the normal one. The gender expectation in the proposal is even more damning; a magic question is still a question, but the predetermined answer on the woman’s part is yes, so much so that we feel the rejection on Harry’s end. This makes Ruth the bad guy for saying no, for not wanting a part in the nuclear home. Because hers blew up. As a result, her shields are up. She tells Harry, “People change… and someday you’re gonna change and maybe that new version of you will love me, or maybe it won’t.”

While giving each other space, Ruth discovers something in a cave that the viewer doesn’t see. All we see is after when Harry finds her. She’s distant, despondent. Not feeling like herself. Just like Bea isn’t quite Bea anymore after Paul finds her alone in the woods.

After the inciting incidents, Significant Other and Honeymoon line up nearly in sync as modern updates on Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Harry and Paul, respectively, start to notice odd behaviors that alienate them from their partners. Back at camp, Ruth sneaks up on Harry in the night with a knife drawn, and there’s a long beat before she says, “I thought I saw something.” Harry takes the knife away and they return to the tent where Ruth doesn’t get any sleep.

At the cabin, Bea is pulling away from her husband, where yesterday she couldn’t keep her hands off him. Rose Leslie’s glowing smile falls from genuine to performative. “What happened?” Paul keeps probing. When he asks about her nightgown, which he finds ripped open and slimy in the woods, she says it’s in her “clothes box” instead of “suitcase.” She tells him she’s fine, even when he sees her rehearsing strange phrases in the mirror like, “I kind of have a headache,” or when she starts journaling facts about her life that seem to be slipping her memory. And when Paul tries to resume their intimacy, Bea unconvincingly says she has a headache, and it leaves him feeling like they’re on different planets.

Janiak’s camera is the awkward third wheel in the implosion, while Berk and Olsen’s camera is the GoPro tethered to Ruth. The following morning, Ruth is ready to take the leap all of a sudden. She asks Harry to propose again, back at the cliff where she says yes this time. Then she pushes him off the edge to his death.

The paths of Significant Other and Honeymoon separate in revealing the antagonist. In Honeymoon, it’s clear something’s wrong with Bea. In Significant Other, we’re conditioned to think something’s wrong with Ruth because she appears to be the blank slate in contrast to Harry’s open charm and charisma. After killing him, Ruth runs into an older couple hiking the trail. She points a knife at them, and it seems she’ll do to them what she did to Harry. Then the film zags in the other direction. Harry emerges unscathed from the fall, eager to pick up where he left off with his fiancee. (She said yes, after all.)

The thing we think happened to Ruth instead happened to Harry—a twist that Jake Lacy eats up. (During the reveal, he says, “I come in peace.”) His winning smile was the facade the entire time, and it turns menacing on a dime. While hiking the trail alone some weeks back, he encountered an extraterrestrial that crash-landed in the woods, which killed and replicated him. Ruth found Harry’s discarded corpse in the cave, realizing the horror for herself. The Harry that returned – that she’s been with since then – is not her Harry but a perfect copy. Ruth remained guarded in front of the older couple because she didn’t know if their bodies were snatched up and duplicated either. Her inner horror movie on commitment blooms into a paranoid, on-the-run alien invasion movie.

The alien revelation for Paul comes at the end. Earlier in Honeymoon, they meet a couple in the throes of their relationship—a possessive man and a withdrawn woman. At the time, Bea and Paul used this lovers’ spat to bolster their self-portrait as newlyweds: “We aren’t like them.” They had walked in on Act II of their movie and didn’t know it. Paul seeks the same couple for answers and finds that the man has gone missing. And the woman, also bearing marks on her thighs, clings to similar journal entries of her life. When he checks their security camera footage, she too was lured by mysterious lights.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers may be Honeymoon’s guiding beam, but there’s another alien invasion movie gestating in the concept: Gene Fowler Jr’s 1958 film, I Married a Monster from Outer Space. Gloria Talbot’s Marge suspects something’s wrong with her husband Bill (Tom Tryon), who hasn’t been the same since the wedding. She discovers he’s an alien imposter along with other husbands in the town. These aliens invade because the females on their planet died out and have launched a breeding plan on Earth.

Whether this is the goal of the “visitors” in Honeymoon, it’s left to nightmarish interpretation. But having lured one woman on the lake plus Bea, perhaps the end design is the same. In the final confrontation, Paul ties his wife to the bed. She finally tells him what happened, that the visitors are coming to take her away, and he discovers the worm-like creature inside her.

In Significant Other, Ruth gets engaged to a monster from outer space. Alien Harry tells Ruth that the invasion is coming and offers an out-of-this-world proposal: to run off together in his spaceship. When she leaves him at the space altar, he decides that if he can’t be with Ruth, he’ll become Ruth. It’s the ultimate act of true love in his eyes: “Hunger passes when we eat, exhaustion fades when we sleep, but that’s not true for love. That’s what makes it so unique. The goal is unattainable. It’s two souls desperately wanting to become one.”

This is where Significant Other joins in lock-step with its body-snatching peers. In the 1993 Body Snatchers, imposter Carol (Meg Tilly) says to her human family before emitting the hair-raising Pod shriek: “Where you gonna go, where you gonna run, where you gonna hide? Nowhere… ’cause there’s no one like you left.” She’s speaking of the inescapable terror of conformity, but it could easily be the next stanza in alien Harry’s treatise on love. (Or a mic-drop in someone’s wedding vows.)

In I Married a Monster from Outer Space, as the aliens gain access to the humans’ bodies and memories, they begin to experience human emotion. When Marge rejects alien Bill’s plan to repopulate his species, he’s genuinely hurt by her rejection. Similarly in Significant Other, alien Harry winds up a victim of the human body. In becoming Ruth, alien Ruth becomes painfully human, absorbing her thoughts, her memories, her anxieties. (As Will Smith’s Captain Steven Hiller in Independence Day would say, “Welcome to Earth.”) Alien Ruth succumbs to the crippling voices and real Ruth puts her out of her misery.

Both protagonists and the promises they made to their significant other are put to the test. Ruth goes on the hike of her life, one she’ll never forget, while Paul gets all the time in the world to explore his wife’s body, to his horror. Ruth survives Significant Other by maintaining her individuality. Paul doesn’t in Honeymoon because he refuses to part from his wife, like a dutiful husband. Unfortunately, he becomes shackled to his ball and chain for good. Bea, now a husk, ties an anchor to her husband’s feet and throws the only remaining human of the two off the deep end, a bleak finale that suits the 1978 ending of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Jack Finney’s 1954 novel has been adapted for different eras, embodying metaphors for invading political ideologies, nuclear anxieties, encroaching government bodies, and conformity at large. Significant Other and Honeymoon show how remixable Invasion of the Body Snatchers is as a concept, malleable even for millennial paranoias surrounding the institution of marriage. The premise is timeless… or a tale as old as time. Significant Other and Honeymoon probe the millennial anxieties of domestication and tying the knot, not knowing our partners as well as we think we do, and how moments big and small can alienate two people. Extraterrestrials may be in the mix, but the fissures that lead to our undoing are strangely human.