She’s too hot to handle.

“It was a pleasure to burn.” Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

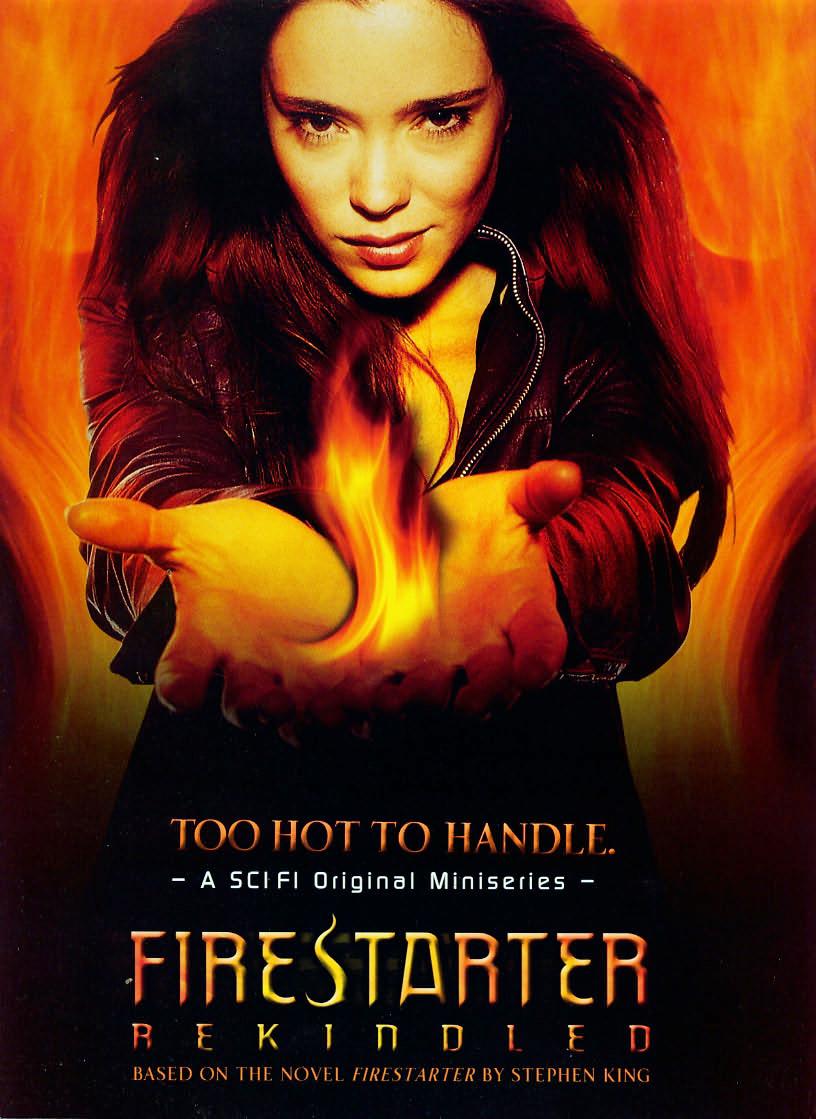

Firestarter is Stephen King’s hottest novel, literally. Originally released in 1980, it’s the story of Charlie McGee, an eight year old girl with pyrokinesis, the ability to light fires with her mind. Though King’s original story is far from sexual (its protagonist is a child, after all) the pages burn with the fire of feminine rage. Charlie has been taught since birth to fear her body’s power and her climactic destruction of the control she’s been raised with is an allegory for burning down the patriarchy itself. Though King’s original story and the subsequent film adaptation are filled with repression, the 2002 Sci-Fi mini-series Firestarter 2: Rekindled is bursting with heat. Now an adult, Charlie McGee (Marguerite Moreau) lives a solitary life researching the government experiment that altered her parents’ gene structure and led to her phenomenal psy talent. Though the two-part series has many flaws, its first episode explores Charlie’s tendency to create destructive fires in the throes of sexual excitement, leading to an intense fear of intimacy. Her inability to come is not only tragic, but a manifestation of her repressive upbringing and a representation of cultural panic surrounding the concept of female orgasm.

Firestarter 2: Rekindled catches up with Charlie years after the cataclysmic fire she caused while escaping the notorious government agency known as The Shop. Finally unleashing the full force of her powers, she burned down the entire complex, killing many employees along with Rainbird (Malcolm McDowell), an assassin who gained her trust in an elaborate plot to kill her. Now in her early twenties, Charlie lives a nomadic life and sleeps with a fire extinguisher by her bed, preparing for the blaze her nightmares will inevitably cause. She’s taken a job at a university library in order to study the work of Dr. Wanless and the Lot 6 experiment that led to her conception. She has vowed never to use her powers and lives under an assumed name, believing herself to be a danger to anyone who gets too close.

But Charlie is also human and lives with a natural desire for connection. While shelving books, she lingers near a couple canoodling in the stacks. Though she says nothing, it’s clear that she longs for this kind of intimacy. Soon after, Charlie is dancing alone at a nightclub when she’s approached by a strange man. She tentatively touches his face before passionately kissing him, rubbing her body against his. This quickly leads to making out in the parking lot, and they seemingly intend to have sex on the hood of a car. Climbing on top of him, Charlie is fully in control and enjoying the physical connection. But she suddenly stops herself and pulls away. As if realizing what she’s about to do, Charlie runs down the nearby alley as the man calls after her. She turns the corner and lets the fire roll through her body. Leaning against the brick wall, she experiences what can only be described as a firegasm, physical pleasure that manifests as rapidly spreading flames at the climax of her pleasure. She walks confidently out of the alley as the flames spread behind her, destroying everything in their path.

This scene is interspersed with flashbacks of Charlie as a child. Her father, Andy (Aaron Radl), shakes her and demands that she stop the burning, but a dazed Charlie refuses. She obviously gets both physical and mental pleasure from an act her body was designed to perform, but she has been taught to fear this ability. As a baby, Andy instilled a system of shame and negative reinforcement intended to make his daughter afraid to light fires. While this is a reasonable response to an infant with a deadly gift, he does not adjust his teaching as his daughter ages. The adult Charlie enjoys the orgasmic experience of burning, but part of her still feels like the little girl berated by her father for expressing herself. This internalized shame is a message most girls have been raised with since birth. We are taught to protect our purity at all costs and to view our sexuality as shameful and even dangerous. Rape culture positions men as seekers of sexual pleasure and women as guardians against it. We are the prize, never the pursuer. And once we’ve been caught, ideally through the contract of marriage, we are the givers of pleasure, not the recievers. Charlie challenges this reductive norm by daring to enjoying sex with a stranger and immediately feels guilty for her perceived transgression. She sees the destructive fire her sexuality causes is a physical manifestation of her “bad” behavior.

Andy believes he is doing what’s best for his daughter, but his attempt to control her is in line with historical examples of gender-based oppression. Many conservative religions are founded on the idea that sex should be reserved for reproduction. Since only male orgasm is necessary to conceive, women’s orgasms have long been viewed as unnecessary and even sinful. In fact, as late as the 20th century, many doctors believed that women could only achieve orgasm through vaginal penetration. Clitoral climax was viewed as a sign of physical or mental illness, with cures ranging from exorcism, institutionalization, and marital intercourse. The grand design of this stigma has always been to keep women from enjoying sex. We can draw a direct line between recreational sex and the demand for reproductive freedom. But conservative cultures fear women empowering themselves to survive without men, thus throwing off the system of patriarchal control on which society is built. Even today, the word hysteria is defined as a state of uncontrollable emotion, a female centered term implying the danger posed by an unmanageable woman. Charlie fears her fiery climax the way women have been taught to fear their sexuality since the origins of human history.

But a second encounter gives us hope for Charlie’s empowerment. She becomes close to a man named Vincent (Danny Nucci) who has been sent by the new manifestation of The Shop to kill her. The details of this ridiculous plot don’t matter, except to say that the two hit it off and Charlie begins to trust him. While talking in Vincent’s hotel room, Charlie leans over to kiss him. The encounter escalates as they turn off the lights and prepare to have sex. Once again she feels the flames growing within her and freezes in fear. Claiming that she doesn’t want to hurt him, she bolts down the hall. The room is still intact, but after turning on the lights, Vincent sees that it has been badly burned. The wallpaper is scorched, the pages of their notes have yellowed with heat, and the phone is melted to the point of destruction. Despite this extensive damage, Vincent himself is unhurt. Yes, he’s a little sweaty, but that’s to be expected given his most recent activity. Charlie too remains unburned by her own fire, evidence that she may have the ability to extend this protection to an intimate partner. It’s also likely that had the encounter taken place in a fireproof room, she and Vincent would be able to find a satisfying climax together. Unfortunately her deeply held fear prevents her from seeing this as an option.

Given the amount of destruction her firegasm causes, it’s reasonable to assume Charlie might want to avoid sex all together. But this is the same thinking that causes her to fear her abilities in King’s original novel. An early scene in the mini-series shows her waking from a nightmare to find her bed in flames. As a matter of course, she uses a nearby fire extinguisher to put it out. Though they are different functions, both sleep and orgasm involve a loss of bodily control, but Charlie does not deny herself the pleasure of sleep. She simply finds a way to manage it. Could she not take this same approach with her sexuality, experimenting in water or stimulating herself in increments and noticing any trends in the heat she produces. But she chooses to abstain. While this is ostensibly because she doesn’t want to hurt Vincent, the deeper reason is likely her father’s shameful conditioning. Any experimentation would inevitably lead to an activity she inherently believes is bad.

The mini-series essentially abandons this storyline and though Charlie and Vincent remain close, they never again attempt physical intimacy. However, in a bizarre conclusion, Charlie kills Rainbird by directing her power through a kiss that incinerates him. This proves that she is capable of controlling her pyrokinesis in an intimate setting. Perhaps she will use this as a catalyst to further experiment with the range of her powers. The tragedy of Charlie’s life is that she believes she must figure all of this out on her own. Having suffered immense trauma at the hands of The Shop and psychological damage inflicted by her father, she believes she must deny herself one of life’s great pleasures. And she is far from the only woman to prevent herself from having an orgasm because of a deeply held belief that it is bad. But Charlie is just as deserving of sexual gratification as any one of us. She deserves love and she deserves to have an orgasm without guilt, fear, and shame. We all do. King introduces his novel with Ray Bradburry’s famous quote, “It was a pleasure to burn.” We can only hope that having incinerated the internal walls of patriarchal control, she can cast off the shame she was programmed to carry and fully explore the pleasures of burning desire.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/01/15/049/n/1922564/a753b85967884eaf8fe5f9.34920179_.jpg)