F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu is a masterpiece of silent cinema. It’s one of the all-time great horror films. While it did not get the rights to the characters of the novel Dracula from the Stoker family, it is nonetheless a solid adaptation of the tale. The production design, cinematography and lead performance from Max Shreck are as eerie as can be. So, it may surprise you that I find Werner Herzog’s 1979 remake to be the better piece.

Nosferatu the Vampyre was made a long time after Murnau’s, but in some ways feels almost as if it came from the same era as the original. The remake is heavily reliant on the score, exaggerated light and shadows and over-expressive actors. It’s very respectful to the source material of both the silent film and the original novel. Given that this production was done after Dracula had become public domain, the characters in Herzog’s version–at least for the most part—retain their original names.

More than anything, the success of Herzog’s Nosferatu lies in its uniqueness. While it respects the original, it still has a visual style that is entirely its own. It is slow-paced, but moves in perfect timing with the haunting score. Like many European horrors, the plot is not as important as the imagery, which fits perfectly here. Everyone knows the story of Dracula and while this adaptation doesn’t dwell too much on certain aspects of the tale, it doesn’t outright ignore anything either.

If anything, Herzog’s Nosferatu strips the story down to the essentials. Four major characters from Dracula are retained and become the focus: Jonathan Harker, Lucy Westenra, R.M. Renfield and Abraham Van Helsing. This works very well, given that these were the four characters that were renamed in Murnau’s Nosferatu.

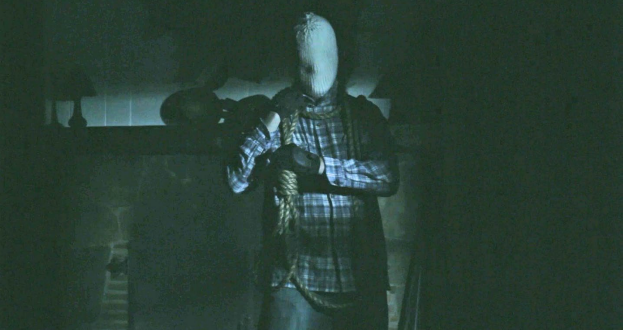

Each of these characters stands on their own, but it is naturally Klaus Kinski as the vampire that remains the most memorable. Kinski’s performance is animalistic, horrific and deeply sad all at once. There’s a much more heightened connection between the Count and rats here than is seen in other films. Kinski’s performance is very rodent-like in nature.

At the same time, he is human despite his monstrous appearance. Nothing the Count does is portrayed as justified in any way, but the viewer makes enough of a connection with him from his performance and mannerisms to be able to feel something for his character.

Lucy stands out as a very unique lead when compared with other female protagonists from the various Dracula adaptations. Her performance is exaggerated, she’s wide-eyed from practically the beginning to the end, but she also has a cold sense of determination.

Lucy stands out as a very unique lead when compared with other female protagonists from the various Dracula adaptations. Her performance is exaggerated, she’s wide-eyed from practically the beginning to the end, but she also has a cold sense of determination.

The cinematography is one of the main things that stands out about the film. It’s absolutely gorgeous. Some adaptations of Dracula lose their visual flair after the opening in Transylvania, but this one remains stunning throughout. The scenery is beautiful, the camerawork is methodical and the entire thing feels choreographed like a ballet. Herzog is a brilliant director in this regard and his talent is beautifully showcased here.

The standout scene sees Lucy walking through the streets and watching the suffering of those affected by the plague sweeping their city. The movements are so perfectly timed, the cinematography so in synch that it truly feels like a dance. Scenes like this are what make Herzog’s Nosferatu so powerful and ultimately better than the original.

The standout scene sees Lucy walking through the streets and watching the suffering of those affected by the plague sweeping their city. The movements are so perfectly timed, the cinematography so in synch that it truly feels like a dance. Scenes like this are what make Herzog’s Nosferatu so powerful and ultimately better than the original.

Mind you, this is not a case of one movie being bad and the other good. Murnau’s Nosferatu is truly exceptional, it stands the test of time when so many silent films have fallen out of memory. Herzog’s feature respects everything that made Murnau’s a masterpiece, but it is its own creature. The cinematography, actors, locations and score all work in perfect synchronicity. It’s one of the best adaptations of Stoker’s novel in general and should not be missed.

Post Views:

1,656